Magda Feeds the Cats

Author: © Liora Sara Bernstein

Adapted to English

Originally in Hebrew:

http://www.literatura.co.il/website/index.asp?id=14758

http://www.tzura.co.il/tshsd/yezira.asp?codyezira=26058&code=3497

For many, many years, Magda would feed the cats.

This custom of hers came sudden and unbidden, like a weed springing up into the world out of nothing, taking the earth in the garden by surprise.

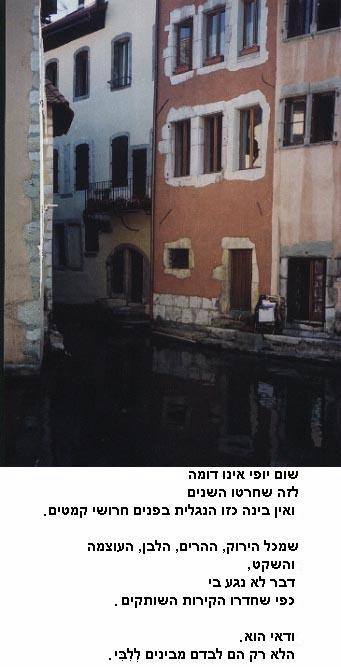

Magda`s earth was like a fallow field, brown and natural and uncultivated. It resembled the façade of a building in a nondescript town where visitors were greeted without the affectation of sprinklers, decorative bushes or a gardener, while the tenants seemed to have flung their hopes up to the heavens, asking for nature`s grace and favors to be delivered unto them without any human intervention.

When this habit first took root in Magda - like a wild weed or, as some might say, a noxious weed - it was alive and green and dispelling bleakness and she didn`t have the heart to destroy it.

The other tenants in her building didn`t know what attitude they should assume to this deplorable habit. When they first noticed her activities, they thought it was a passing fancy, a one-time, once-in-a-while impulse, a fleeting seasonal crisis, an eccentric woman`s whim; but when they realised the activity had become a regular habit, they began talking behind her back and turned their faces away from her if they chanced upon her.

As time went on, some neighbours threatened and vilified her; others suggested, with a smile on their mouths and a friendly expression on their faces that she take the cats with her into her living-room; some complained on the phone to the Municipal authorities and asked that the activity be removed elsewhere rather than in their yard. One morning she even found a mysterious package lying on the steps in front of her door, wrapped carefully in a nylon sheet, with at least a one and a half kilo of rotten sausage meat covered with a layer of white mould in it, - an anonymous gift to the street cats or perhaps a veiled threat in the form of a sliced-up animal.

Over the years, Magda developed a daily routine comprising the cats in it : she would get up early in the morning, almost at sunrise, sweep her home and prepare it for a chance ring at the doorbell; from her window she would observe the street-cleaners, equipped with little bins on wheels, brooms and long-handled scoops; she would watch the municipal workers as they entered the courtyards of the buildings and dragged out the garbage-containers to the edge of the pavements, she would peep through the curtain at the routine scrounger who lifted the lids and scrabbled in the bins searching for hidden treasures and watch how the cats followed close on his heels and jumped into the jaws of the bins scavenging for food discarded by humans from their plates.

Towards about eight o`clock, the other tenants` cars would depart from the parking lot on their way to work and all those activities would cease.

Then, when the empty bins had been restored to their concealed places, and the observant and curious eyes had disappeared, Magda would go down the steps outside into the street, armed with a large square plastic box and a spoon, to the corner, where some of those miserable creatures would be awaiting her, and there she would portion out their food on the pavement with the spoon and return to her home.

And this habit of hers clung to Magda and became part of her personality, like a colored thread woven into a modest fabric, and it stayed with her during her two short marriages, when she moved houses, when her hair changed lengths and colors and when her body filled out. Even when she had found herself a lucrative profession and had a family to visit on the Saturdays and the feast days, still she would persist in this activity, which she had now adapted to her leisure hours. And it was amazing was that this woman, this quiet and unobtrusive woman, did not defer to the wishes of the community and refused to bow to its critical stance.

One day, on her way home from the neighborhood store, Magda decided to stray from her regular route and take a slightly longer road. It was a golden sunny day, hidden bubbles of energy darted in the air like sparkling wine, and Magda, her hands not over-burdened with packages, felt light-footed and heady, and suddenly yearned to do something different. So she turned left from the pavement into the old park by the post-office, walked the length of it, looking around her at the wooden tables, empty of nannies and nursemaids at that hour, and started her way up the little street to the top of the long hill, to reach her home from the back; in other words, a little jaunt to sustain her soul.

For during the past few months many changes had been witnessed in that high piece of ground that beckoned to her, a street whose official name was graced with the word "avenue", thought in fact it sprawled over a long, wide space, covered with pebbles and thorns and few eucalyptus trees of great dimensions, while its other half, the section of the avenue that had inspired such a soul lifting designation from the Municipality, lay across the street some distance away from there. Thus it became an unholy mixture of desolation and cultivation, like some mermaid whose lower torso is a scaly, cold, wet fish while above the waist she is a pretty young girl, whose wild-hair cascades over her beautiful, naked breasts. The lucky people who had bought villas in the avenue more than twenty years earlier had been waiting for salvation to arrive there in the form of paving stones and municipal gardening, and they might have gone on waiting forever had not some well-to-do people and renowned philanthropists settled there, and raised funds in memory of their dearly departed ones now in the hereafter, and also graced with their contributions the little synagogue hidden modestly in a semi-cellar basement with lowly looking entrance, which was situated at the rear of a nondescript girls` school for religiously observant girls.

And from week to week there began to appear in the area alluring visions and lavish sights such as had never before been seen or heard of in the ancient, non-refurbished corners of Tel Aviv. This is where Magda went.

There was an attractive stone fountain that gurgled its fine odor of chlorine in front of one of the villas with an eternally evergreen plastic lawn laid out below it; there were thick, luscious bushes planted around its hedges suckling from the earth, accompanied by clumps and bundles of reeds and decorative plants in planned riotousness; at the bottom of the hill, slightly further down, there stretched handsome living lawns and shrubbery corners and in the centre of a large circle in the midst of the homes, lay a pleasant pond, about two-by-three meters large, which too had been built by a philanthropist for the benefit of the public and the community and who had it surrounded by benches for the use of young ladies and boys of their choice to meet in the mornings, when they played truant, or towards nightfall.

Above all these there towered a stone cast memorial sparkling with mica quartz and adorned with thick copper letters, in memory of the deceased.

And this was not the end of it. The philanthropists` contribution continued to spread towards the right, reappearing further up in the form of a large playground for toddlers with benches for their mothers to rest on. Here there were swings, slides, small carousels, and even a drinking fountain. The old eucalyptus tree was not uprooted, but was surrounded by a wrought-iron grille while a twisted path wound its way, like in the fairy tales, between the young trees recently planted in their pits and among the olive trees that grew there saved from the fury of the wood-chopper. Wide beds of geraniums gave off their perfume for the pleasure of visitors to the little synagogue whose youthful days had returned.

And everything was tight and compact in this small area, here, in the wonderful, unexpected luxury of the rich, a wonderfully pretty and European place to go to in the afternoons and relax, or so Magda felt, in the tiny, hot, oriental country of Israel, in Tel Aviv, where every square inch of land is rare and expensive and there are no two water outlets, a pond and a fountain, in such close proximity and so privately arranged in the entire city…

Magda began to make pilgrimage to that hill, to the "Tzameret", the “Heights”, as she called it, especially on days when her heart widened out in a song like a chick opening its gaping beak to its mother, and then she, Magda, would take her heart to the garden where it would fill up, engorge and be satisfied.

On one particular day, however, which had started out as a simple communion with nature, it was ordained that this same Magda would serve a higher purpose. As she sat relaxing on a bench, breathing in the cool autumn air and filling her heart, her eye fell upon a miserable, thin little kitten, circling around its emaciated mother, and it was clear to her, though nobody would know how, that there was no milk in those teats, while the female cat seemed very ill.

Since her heart did not allow her to ignore them it was thus that now Magda changed her old habit, and from that day on, she set out after work with her ancient plastic box and spoon to that garden, to feed the cats, to ensure that the orphaned kittens would not die of hunger, and to pour water in plastic dishes to quench their thirst. And she always made sure to take out enough for the cats waiting near her home too.

Magda was happy with the change in her daily routine. It satisfied her because it combined several desirable activities, such as a daily fifteen-minute walk in each direction out in the open air – a healthy activity by any standard – and placing a distance between herself and her neighbours by conveyed her `madness` (having no other name for it except the one the neighbors gave it) elsewhere, to another, bigger and more suitable location. There she could devote herself to her activities and enjoy herself without concern or pressure. In any case, she did not seem to have another alternative.

The readers, who have been bearing with us all this while, may ask us to pause here, so that they may ask a few questions such as;

"What does she look like?"

and enquire "What? She goes there every day?" "That Magda?"

As for their unvoiced thoughts, however,– these can only be guessed at or imagined, each reader according to his or her nature and inclinations.

Magda was a handsome, tidy looking woman. At the time of our story she was already past her prime. And yes, she did go there every day, at about four or five o`clock in the afternoon, depending on whether it was summer or winter time, since she adjusted herself to the cats’ internal clock, which was not regulated by human requirements. Whenever she traveled abroad, she would take the trouble to tell people whom she didn`t even know by name, that she, Magda, would be away for a few days, or weeks and that was that.

Her separation from her foster-charges was always difficult and worrisome, but when she had left she would not think about them anymore and when she returned, she would resume her routine.

Thus, Magda resembled two Magdas, both of whom took residence in her body, each one being well aware of the other. Magda would sometimes wonder how it was that she had been found worthy of such merit by the good Lord, or the Infinite Cosmic Consciousness, that she was so favorably weighed in His Scales that He bothered to bestow upon her one and single body two users. In her lesser spiritual more earthly moments, when a wall between her spiritual and practical natures arose within her, she would analyze her situation in logical and academic terms and wonder whether an additional –perhaps unwanted – sliver of personality had settled inside her; or she would consider how she might be better off, in her present dual condition or if one of those Magdas was excised from her being; or speculate whether the two could be made to combine or when and where, if at all, they had at first split up and gone their separate ways.

Thus, the two Magdas went about their – her - business – businesses -, caring for cats and feeding them. They would chat with the people in the garden, at times this Magda was talking and at times the other Magda, and nobody paid attention or realized who was speaking to whom, or who was answering what, since it was inconceivable that nature had granted an additional personality only to her, while it discriminated against the rest of humankind. There must have been more doubles concealed amongst the visitors to the garden, or at least there were some, more cases like hers, who lived at peace with themselves and their additional selves, or may have even been conflicted with their additional other yet they were still two and not one, like the heroine of our tale.

Magda liked the place best when it was empty of people, because when she arrived the cats would emerge from their hiding places and the crows would fly down and be transformed from distant dots in the sky into birds as large as chickens, landing on the street signs and lampposts, in expectation of food. The orderly feeding and closeness were easier and pleasanter when there were no children running around.

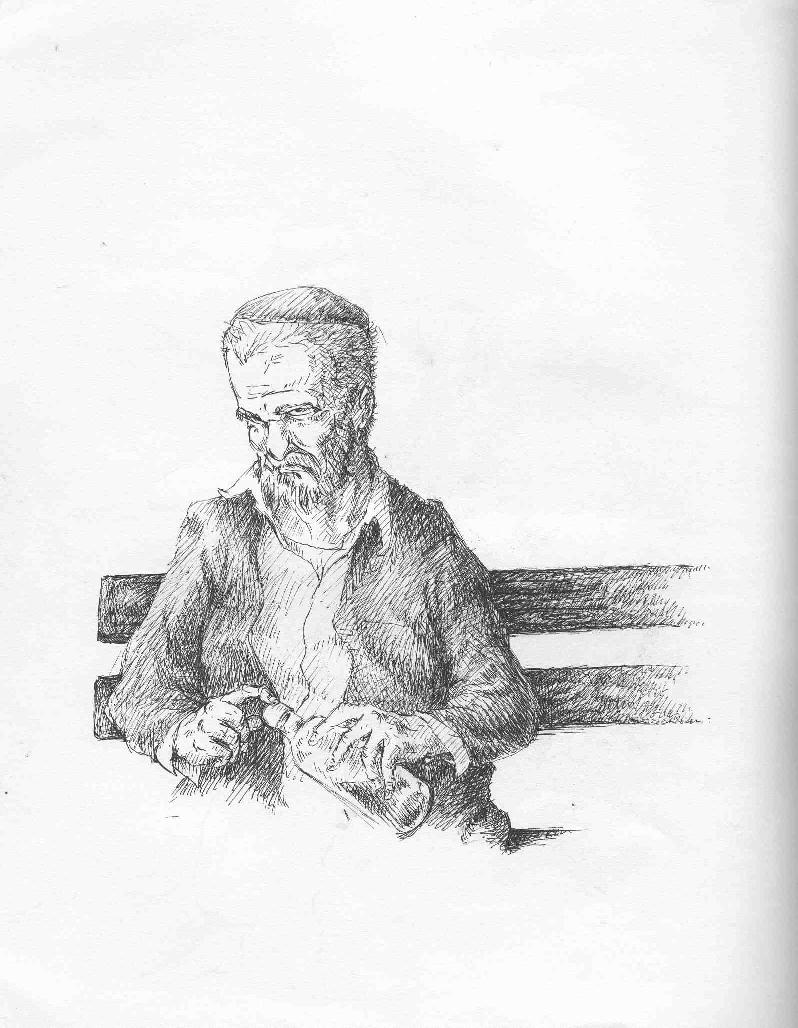

So, on one of those days, in the afternoon hours of the month of Heshvan (around November), Magda was sitting on a bench with her familiar plastic box at her feet, contentedly observing the cats, which were scattered here and there around the corners of the garden, each next to its own little heap of food that she had provided. They concentrating on the food with exemplary order, not scrabbling amongst themselves, but rather like a quiet, disciplined school class on an excursion or at lunch-recess, except that they did not chatter or make a noise like children.

There were not many nannies or children in the playground at that hour, but it was not empty. She spotted a young girl with three children of pre-school age with her, a boy and two girls. Magda couldn`t decide whether the young girl was an older sister or a child-minder. She wore closed shoes, stockings, a long, tubular skirt of milky-tea color with a delicate pattern of small checks in the fabric, and a long-sleeved blouse of similar color, with traces of pink in the dominating milky-brownish hue, tucked into her skirt. Her face was smooth and unblemished, and her eyes were serene and pleasant. The two girls that were with her did not seem unusual to Magda, but the boy caught her attention again and again. For he had large, transparent, blue eyes, perfectly round like a doll`s, that somehow didn`t fit in with his face, and both he and the young girl seemed to be radiating around them a clear, transparent, invisible light.

And different kinds of people used to visit the garden at different times:

In the mornings, for instance, the place was empty and somewhat abandoned, like a housewife who hadn`t as yet put on makeup or dressed herself in her street-clothes to show herself in public. At about eleven in the morning, some youngsters would arrive, who perhaps had had enough of school for that day and escaped to the garden benches for a smoke, or a cold drink, or to gurgle a narghil, the native word for a hookah. At these times there were no toddlers or nannies in the garden – they had moved to another, more shaded park across the street where the older youth did not go.

Another group of people would get there at odd hours during the day, men and women accompanied by all types and kinds of dogs, large and small, on a leash or free-roaming, which were brought there to liberate their limbs and evacuate their bodies. The Municipality had placed a conspicuous, large "Poop-bin" painted pink at the top of the path, for the comfort of these animal-lovers, where they were supposed to dump their pets` excretions. "You don’t mess up in Tel Aviv" warned a green sign, bisected by a line and sporting two bright-looking icons on either side, leaving no doubt as to how to deal with dogs and their poops, before and after. Municipal inspectors also roamed around, dishing out fines to transgressors, steeper than traffic fines.

Yet is not our intention here, heaven forbid, to cast aspersion at the municipality or its Sanitation Department. These dedicated, righteous workers love all mankind and animals equally and perform their creditable deeds, funded by our municipal taxes, on the stray cats, by lopping off a bit of their ear after having sterilized them and then releasing them in the very place where they had been trapped, so that people like Magda can tend to them and care for them while the animal food and pet stores can make a living out of them and bless them, and the veterinarians and animal pounds can shelter them and watch over them with love and all those people can be kept well and busy and stay employed unlike so many other unfortunate people in our country.

There also was a group of people who apparently just seemed to have come to the garden through a kind of private internal daily schedule of their own. From time to time they would confide in Magda, sharing with her secrets about events that had no place of existence in the realms of cultured people and the media, and deposited these unarchived moments in the memory-bank of the cat-feeder who always seemed to be there for backup, thus making them real. For this is a profound and loaded question: do things really exist if no-one knows about them or remembers them? If a tree falls in a forest where no-one hears it, is there a sound to accompany the crash or isn`t there?

In one incident, for example, just so the reader who is scampering behind the thread of the story does not complain, there were those two women, probably in their forties, who occasionally went for a walk along the path at twilight; Magda would nod a greeting to them, and they to her, and whenever they remembered, they would add a "Well done!" exclamation to her feeding while she would reply with an appropriate expression, such as, "Yes, cats are talking animals".

Then, as if to confirm her words, a cat with nipped-off ears, a testimony to the activities of the Tel Aviv Municipality and its veterinarians, would appear. It would purr and meow – ascending and descending emotional scales gushing from its throat - with so much significance concealed behind its tongue that it seemed clear that if only it were created with just a pinch more of grey cells it would be able to express itself in a comprehensible language

Those women once told her –

“you wouldn`t believe it,” said the first,

“yes, I was there,” confirmed the other –

…that one day, while they were resting on one of the benches, to smoke a cigarette or just stare into the air, and the place was empty of people and children, they saw two cats, males or females – who knows – entertaining themselves in the playground installations. One cat waited on the sand at the foot of the slide while the other stood at the top and then slid down. They did so a couple of times. It was something nobody would have believed them if they had told it, and it was insignificant, could be recounted in one or two sentences. Even Magda, whose experience with watching animals was plentiful, had never seen or heard of such a thing ever and might have dismissed such a memory from her mind, but it is written at the mouth of two witnesses shall a matter be established and she believed them.

Two main groups of people who frequented the garden were, of course, the children who came to the playground in the afternoons; the other group came from the religious-observant community that congregated one way or another around the little synagogue and its children, who played in the playground as well. Towards sunset the men would also arrive, in their various attires, and converge in the direction of the synagogue.

Of the different groups of children who came to the park Magda preferred those who had had a religious-observant upbringing; they seemed less menacing to her. When a secular child would shout, "Shoo! Shoo! Kishta!" and stamp his or her feet and interfere with the feeding, she could say at best, "That`s not nice, let them eat", that is, if the adult with him hadn`t reprimanded him, and even so, only if the adult seemed tolerant and unopposed. But if a child of the other kind behaved in this fashion, Magda had a winning argument, and would tell the child, "That`s not nice, weren`t there cats in Noah`s Ark?" So in this matter she felt that with them she had an excuse, an explanation and a defense for her love of animals.

The little boy with the round blue eyes acted that way too. He stood rooted to his spot, quivering like spring, and though a movement was hardly perceptible in him one could see that he was stamping and waving and jumping and hopping, even though he didn`t do any of those things and just stood on the same place, hardly moving, as he throbbed like an electric machine connected to power and followed Magda with his eyes. He too was glowing. She may have imagined it, though. The two little girls in his company stood behind him, like a backdrop for a photographer`s portrait, watching Magda with their little faces leaning towards each other, and above them rose the figure of the calm-eyed young girl in the tubular skirt. She too seemed to radiate somewhat, like the boy. The boy held her hand and pulled her towards the cats, she bent down and whispered a few words to him, surprisingly in English. Magda repeated her usual statement on Noah`s Ark, and moved away a few steps to conclude her business. And that`s how it ended. And he was a child of about three years old, his hair was light brown, almost yellow, he had large, round blue dolls` eyes, side-locks, and a black velvet kippa on his head. Magda, who had finished feeding the cats, turned away from there and made her way home and forgot all about them. It was only later at night, just before falling asleep, when the day`s memories made their appearance before her that the scene emerged before her eyes and her brain filed away the irradiating people in the drawer of irrational personal experiences not accepted by the mind. And there she left it.

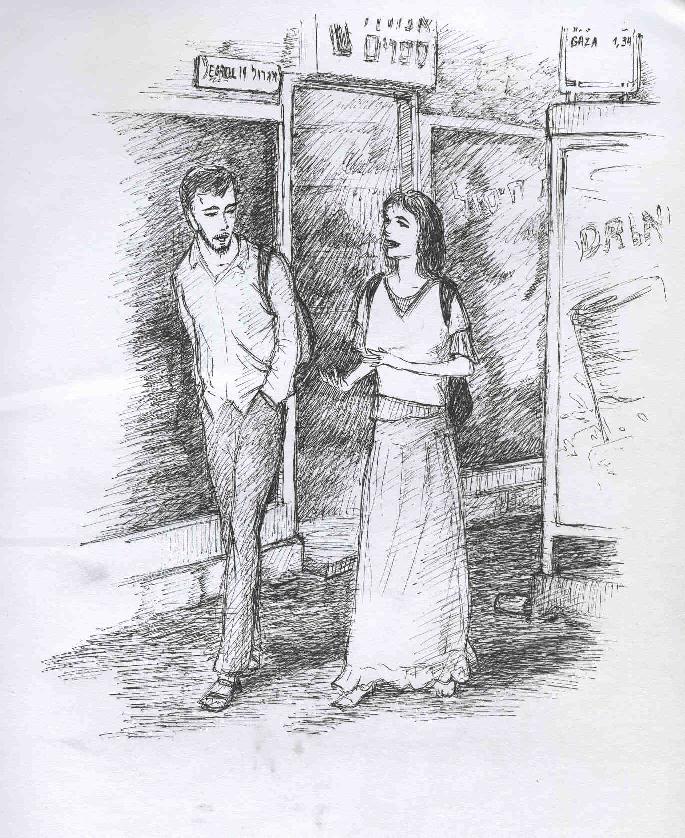

On subsequent days, Magda continued as always with her regular habit, arriving at her destination in the afternoon and feeding the cats, not taking particular notice of the people in the garden or in the playground; neither did she pay much attention to the young girl with the three little ones, although she saw them there a number of times, and everything seemed regular and normal and absolutely acceptable. Until one day, when Magda was standing on the path with her face towards the street preparing to take off the young girl addressed her and asked,

"What do you feed them?" as she peered into the plastic box.

Magda too looked into the box, in which were a few uneaten little swollen brown rings.

And that was a different matter. For when Magda wanted to start a conversation, she would always try to do so from a standpoint of superiority, from a distance, where she couldn`t be reached, in an effort to confuse and bewilder her interlocutor and not allow him or her to interject a critical word about her interest in the cats. Of herself she disclosed nothing, for that`s how she was with people: she did not give – she did not take, she did not ask questions – was not being asked questions. That`s how it suited her. Surely, she felt, there must still be places in the world where a person could retire into an invisible circle of touch-me-not, unlike that little nation by the sea, where so many sucked the essence of their vitality from gossip and professional familiarity with the lives of celebrities, and spent their evenings peering through the windows of their TV sets at the socializing series that united the media culture, while others who refused to take part in this culture turned to the worlds of imagination and fantasy, of computer dragon mazes and adventures, making their way on the material roads of the world through the projections of others without a fragment of light.

This girl did not arrive from such a place. She came from elsewhere, like the cats – with a difference, of course ! – so Magda felt sorry for her and spoke to her carefully and gently as if she were made of marshmallow, a fluffy, woolly delicacy, soft and white, tasty, sticky and sweet.

"It`s cat food," she explained, showing her the contents of the box. "You buy it in a special shop. I pour water on it, because it`s as dry as matza, so it won`t swell in the cats` bellies," she ended her lecture, gave her a quick glance and walked off.

But the next day the young girl was waiting for her, with the little children who were probably in her charge.

"Do you always come here at four o`clock?" she asked.

"Yes," Magda replied.

"He has been waiting for you," the girl explained. "He`s been shut up in his room all day and he wanted to go out. He wanted to watch you feed the cats."

Meanwhile, a number of cats had emerged from among the bushes and approached them, keeping a certain distance, and the boy with the round eyes emitted a joyful, high-pitched cry and ran a couple of steps, stopped and retreated, and ran forward again and stopped and retreated, while the little girls stood watching calmly by.

"Here, come and see how I feed them," Magda said to him, as she doled out handfuls upon handfuls of food, placing them about two meters apart, as she called the cats. She looked at the young girl.

"He`s not allowed to touch them, right?," Magda asked and the girl nodded silently. For Magda knew, what some may not know, that in their eyes cats are impure, and some even believe they steal away one`s memory. The boy watched, standing again rooted to the spot yet seeming to be quivering like a spring, and Magda felt sorry for him too, wanting to shield him from an accusation or guilt – for this is how she understood it – that this child didn`t want to stay shut up in his room at home, studying perhaps or sitting quietly, for who knew how he was being brought up, and she hunted for words that would be appropriate to the spirit of this pure young girl who didn`t know what cat food was and suggested to her, in the boy`s defense,

“It fascinates him. He is still small. He is very young and it fascinates him because he is still nearer to creation,” she said to her with a meaningful glance, hoping there was a line of communication between them.

"Why don`t you bring him here a scooter, or a bicycle, or a tricycle, so he can expend some energy, make an effort, ride around?" she suggested.

"He does have a bicycle," replied the girl, "but he doesn`t like to ride alone

"So bring one for his sister too," Magda dared to suggest, although she didn`t know whether small religious-observant girls in skirts were allowed to ride bicycles. "They could ride together. Is that his sister?"

"This is his sister, and that`s a cousin," replied the girl.

And that was how that encounter ended and Magda made her way home but, for some reason that she couldn`t quite fathom, the young girl and the little boy had lodged themselves in her thoughts.

That night, before she fell asleep, they began to flicker under her closed eyelids on her screen of memories, and her brain began to weave sensitive, romantic scenarios around them, where the boy was a future Head successor of a large Yeshiva in the United States, whose family, or at least some of it, was then in this country for unknown reasons, and he was the descendant of Geonim and Rabbis, being shut up at home all day long, where his eyes encountered only bare walls and rows upon rows of bookshelves weighed down with spiritual books, and he already knew prayers and prohibitions, and the young girl was his older sister who looked after him, and both of them were biblical creatures with little knowledge of what went on around them in the secular streets of Tel Aviv or how people behaved there or what they were selling in their stores, and they certainly were not knowledgeable of the news on TV, of trivia games, soap operas or mere scenes of lewdness that should not be mentioned to them and from which they must be shielded.

For in fact, they were like the cats and other creatures that needed to be protected from humans. And the chasm was so huge and powerful between her and them that it was amazing how they had opened up the gates to her imagination, and she herself may even have been in their thoughts at that moment too.

Thus it was that Magda met with this little family for about two weeks. And she made an effort to speak their language. When the young girl asked her why she fed the cats, she hesitated, and eventually, as she tried to explain the beauty and the emotion she experienced in doing this, she said to her, as if pronouncing a secret,

"We cannot see the Creator, but we can see His creation."

The girl looked at her and smiled softly, without showing any surprise at her words, and added, unequivocally, "The world has a Master", “Yesh Manheeg LaOlam”, and Magda envied her the possession of that phrase, in the shade of which she had grown up.

She explained to the young girl the significance of the lopped-off ears of the cats, quoting from an item she had once read in the newspaper, stating that two cats could, under optimal conditions, produce about 25.000 cats over a period of six years. "That is why they must be sterilized," she explained, "and then they guard their territory, destroy bugs and field mice, and also become friendly and gentle, because they are no longer ruled by their urges," she concluded her little `expose`.

"That`s a demographic problem," suggested the girl, surprising Magda by her use of that term.

On another occasion, when Magda flung a handful of cat-food up in the air so it would scatter like seeds on reaching the ground for the ravens that always watched from above like a polite, patient crowd of spectators waiting for the cats to disperse, the girl told her a complicated tale about a bird, a raven, that flew over the seas and did strange things, and Magda listened, but couldn`t recall the story. The girl seemed intelligent, apparently with a good brain that absorbed and remembered what she had learnt and heard. She asked Magda if it was true that ravens flew down and pecked out people`s eyes and Magda told her, "No, only if a chick falls out of the nest do they watch it from above so it will not be harmed, and they circle above and appear menacing." Back home later that day Magda looked up an old book entitled "All the Legends of Israel", to see if it included the tale the girl had related to her about the mysterious bird, but couldn`t find it.

The culmination of these happenings was reached when Magda came to the garden one day with her plastic box and found the four of them waiting for her expectantly and the girl said,

"Today we brought a bicycle, like you suggested."

They had a bicycle and a scooter too, and it appeared that even before her arrival, the children had taken turns in riding around, enjoying themselves and tiring themselves out. And Magda`s heart swelled, to think that her words had reached their hearts. And then she did something she shouldn`t have done.

"What’s his name?" she asked.

"Yossi," replied the girl.

And Magda stepped outside the invisible touch-me-not circle that had always surrounded her and went up to little Yossi. She crouched down on her haunches so she could look at him eye-to-eye, and said,

"Yossi, say `Father, bring down the rain`." And Yossi looked back at her and shook his head with a hint of a refusal

"Yossi," pleaded Magda, looking at the young girl, "say `Father, bring down the rain`",

Explaining to the girl, "because it is written that `out of the mouths of babes and sucklings hast Thou ordained strength`."

The young girl`s face lit up, and she too said to him, "Yossi, say `Father, bring down rain`."

But Yossi refused, and Magda felt heavy sorrow and despair descending on her slowly from above, for that year was a year of dreadful drought, and the skies of the month of Kislev were as clear as the skies of Tamuz.

And the next day they did not come any more.

Every day she waited for them to come to the garden, like a cat waiting for the woman-person who brings it food every day who has now disappeared and it awaits his food and its innards grumble from hunger and sadness. And at night her imagination ran riot, and the little boy featured in her visions in the form of "The Chosen" in Potok`s book, who was distanced from love in order to develop the principle of compassion in his soul. She wondered whether the girl had been forbidden to go back to the playground because the people there were unsuitable for her to socialize with, but eventually she regained her tranquility, and forgot.

Several years went by, and Magda was older in years. She had gone back to feeding the cats by the street corner only, near her home, and didn`t go to the garden regularly. One day, however, she happened to walk through it, and stopped to rest on a bench. She saw a cat sitting watching her from a short distance, and she offered it some dry food, as she always kept a small packet of it in her handbag. Then a woman sitting opposite her, rocking a baby-pram, stood up and came towards her. She was a young woman, dressed in a religious-observant style. The woman sat beside Magda with the pram and said,

"You`re the lady who feeds the cats, aren`t you?"

"Yes," countered Magda, "but I don`t feed them here."

"But you did use to once, didn`t you? You used to do so a few years back."

"Yes, I used to feed them here too." She raised her eyes to look into the young woman`s eyes, and then turned them away.

"Don`t you remember me?" queried the woman. "I used to come here with three little children that I minded in the afternoons. With Yossi. Do you remember?"

And Magda remembered.

"Where were you?" she enquired, "You disappeared. You didn`t come any more. What happened?"

"The family went back to the United States," the woman explained. "They had come for a visit at that time, and went back."

"Is that why they spoke English and Hebrew?"

"Yes, at home they spoke English and outside, Hebrew. But they came back to Israel, and today they live in Jerusalem."

"And this is your baby?" Magda wondered politely.

"Yes," her interlocutor replied.

The two women sat in silence looking at the swings.

"You know," said the young woman to Magda, "I gather all the scraps of food at home and bring them inconspicuously to the street corner. For the cats. My husband doesn`t object," she added, and a few minutes later she got up and left.

Thus it was.

And so it came to pass that hard as it was to understand Magda, yet people deposited their special memories with her, and she too was blessed, for her memory too remained with others, with love.

“Yesh Manheeg LaOlam”! The world has a Master.

* * *

To the Reader:

An eBook in English by the same writer is available in: http://www.esfarim.co.il/website/index1.asp?category=11&id=4297

Other English works (non fiction) can be found in:

http://www.literatura.co.il/website/index.asp?id=22159 and http://www.literatura.co.il/website/index.asp?id=22158

תגובות